📔 New Policy Kit: State Service Years

We’ve teamed up with Sam Pressler and Connective Tissue to release a new policy kit on how states can establish service year programs to strengthen connectedness during the adult transition. You can access the full kit here. In the essay below, cross-posted from Connective Tissue, Sam explores the potential for this model to broaden access to rites of passage, fight segregation, promote social solidarity, and transform the adult transition in America from a "great sorter" into a "great connector." —Pete

Building a new rite of passage for high school grads

by Sam Pressler

Our rites of passage into adulthood matter. It’s in this formative period that we cultivate the values, habits, and relationships that ultimately shape the neighbors and citizens we become. Unfortunately, in the United States, our formal structures that facilitate the transition into adulthood are broken.

Just one percent of the population now serves in the military at any given time, and military recruitment numbers continue to dwindle. Four-year colleges have become a “hereditary meritocracy” largely reserved for the children of upper-middle-class and college-educated parents. Those who don’t enlist or enroll are left high and dry: whether they take classes part-time, directly enter the workforce, or don’t work at all, they often aren’t experiencing any collective rite of passage into adulthood.

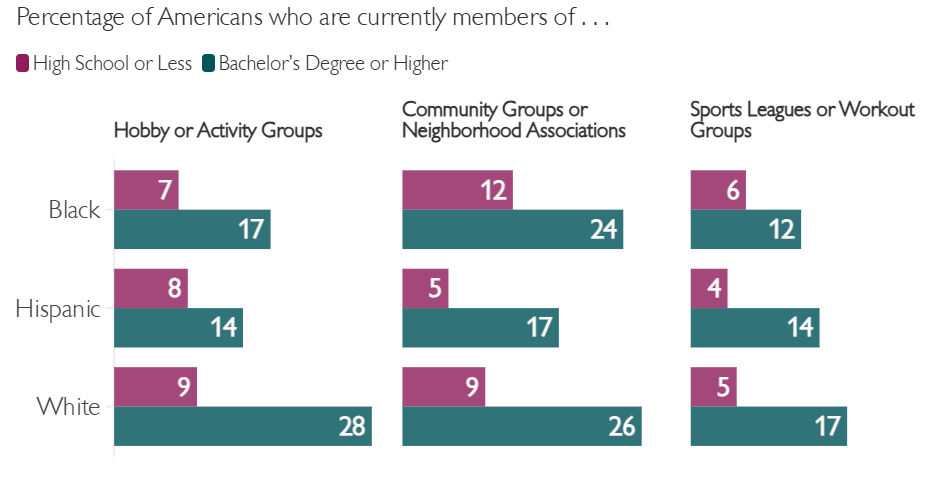

Given this great divergence in communal experiences during the adult transition, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that this period has become the “great sorter” of our social lives. Compared to high school graduates, college-educated Americans are significantly more likely to be members of community groups (25 percent v. 9 percent) and religious groups (39 percent v. 27 percent). They are also significantly more likely to have six or more close friends (33 percent v. 17 percent), and significantly less likely to have no close friends (10 percent v. 24 percent). And, notably, they are significantly more likely to have met their close friends at school (55 percent v. 34 percent), signaling the social importance of this particular transition period.

As I toured the country (via my Zoom machine) to develop the Connective Tissue Policy Framework, governors’ offices across the political spectrum were hip to this reality. Nearly all of them named something along the lines of “reimagining the adult transition” as a top priority for their respective administrations. And nearly all of them saw some form of a state-level service year — paid one-year service opportunities for recent graduates of high schools within the state — as a promising strategy for helping 18- to 22-year-olds cultivate habits of service and forge connections across difference during the adult transition.

But this isn’t just an aspirational idea: Several states are already experimenting with different types of service years. Examples include California’s College Corps, Maryland’s Service Year Option, and Utah’s One Utah Service Fellowship — all launched within the last three years. While states had been creating service year initiatives to complement existing AmeriCorps-funded programs, the recent gutting of AmeriCorps has functionally cut off the federal government as a reliable funding source. Consequently, these state-level service years may become the main option for state leaders committed to promoting service and connection during the adult transition.

With a growing recognition that our adult transition isn’t working, an uncertain federal funding landscape, and policy momentum in states ranging from Maryland to Utah, the moment is ripe for the expansion of these state-level service years. That’s why we’re teaming up with the Democracy Policy Network to publish a new toolkit to help state leaders create service years in their states. The toolkit builds on the “Adult Transition” section of the Connective Tissue Policy Framework, offering a deeper explanation of how states can establish service years that prioritize connection and providing precedents of what this looks like in practice.

The process of establishing a state-level service year could begin with the Governor naming it as an administrative and funding priority. To this end, governors could create a cabinet-level office via executive action to oversee all state service efforts, including the service year initiative. Not only does this demonstrate the program’s importance to the cabinet, legislature, and public, but it also creates the accountability mechanism to encourage state leadership to follow through. In addition to setting up this cabinet-level infrastructure, states should be prepared to dedicate sufficient budget for the design, launch, and execution of their service year initiatives. Funding could come from state appropriations via legislative action, as Maryland did through Senate Bill 551, and through contributions from philanthropy, as California has done through the California Volunteers Fund. By establishing the requisite administrative and funding infrastructure, leadership would be affirmatively signaling: service — particularly during the adult transition — is a top priority for the state.

Getting this structure in place is just the start. If a primary goal of service year initiatives is to promote connection across difference — geography, class, race, and the like — state leadership must intentionally design these programs to promote accessibility and connection. But what does this actually entail?

Designing service years to facilitate diverse socioeconomic and geographic representation involves a multi-pronged approach. Leaders should identify the barriers to participation — lack of access to transportation, housing, and childcare, to name a few — and develop strategies to overcome these barriers (e.g., providing housing or childcare allowances). Program leadership should also conduct outreach with an emphasis on recruiting fellows from lower-income communities, smaller towns, and rural areas. This could range from building trusting relationships with referral partners within these communities, to showing up for in-person recruitment events, to over-indexing on outreach to these places (recognizing they could be underrepresented otherwise).

But it’s not just about tactics; material benefits matter, too. Service years should be designed to provide fellows with a living wage, helping to increase the likelihood that young people from lower-income families can participate without family support. States could also provide alumni with educational benefits — drawing inspiration, in part, from the G.I. Bill — that can be used at state universities, community colleges, and vocational training programs. Maryland’s Service Year Option includes both of these benefits, providing fellows with a living wage of $15/hour and a $6,000 educational award for completing the program. These strategies can make the difference between creating a truly socioeconomically and geographically representative service year initiative, versus replicating another gap year program for the children of well-off parents.

Even if states are successful in making their service years accessible, connection doesn’t just happen — state leadership needs to prioritize connection and bake it into the very design of the program. To this end, program leaders should build service years on a cohort-based model, providing fellows the opportunity to interact, connect, and develop trust throughout the full year of the fellowship. Opening and closing rituals for these cohorts are essential. Cohorts should start with a kickoff summit-like experience to facilitate early relationship-building, and conclude with a closing graduation to celebrate their accomplishments together. Leadership should also create outlets for consistent engagement among cohort members throughout the entire service year, including statewide gatherings for the full cohort on a quarterly basis, and more local gatherings for cohort members one or twice per month. Even if fellows do not all serve together on the same projects, this intentional cohort design creates the conditions for the continual bonding experiences that help deepen relationships.

In addition to the cohort experience, state leaders should consider designing service year initiatives to promote social skill-building. Colleges and the military do this — both directly through training and indirectly through team projects and missions — and there’s no reason service year initiatives shouldn’t do the same. Social skill-building can be embedded as a core program goal during the fellows’ on-the-job placement, and throughout their experience with their fellow cohort. The starting point should be basic social skills — such as how to listen and ask good questions and how to interact with supervisors and teammates — that have been underdeveloped among young people who have grown up in the smartphone era. Later in the service year, program leaders can incorporate skill-building focused on facilitating connection across lines of difference (e.g., class, geography, politics), much like Maryland has done through their partnership with Thread. This emphasis on social skill-building can help fellows strengthen their relationships, not only within the cohort but also long after their service year concludes.

Perhaps you’re thinking, “This is all very nice, but it won’t come close to solving the social sorting and disconnection that is accelerating during the adult transition.” To that, I say: You’re right. This is a problem generations in the making, with several interconnected factors driving it, and it won’t be solved overnight. If we’re going to reimagine the adult transition to promote connectedness for all Americans, we need to be taking an all-of-the-above approach. This means more cohort-based vocational training pathways, more domestic exchange programs for high school seniors and recent graduates, and more opportunities to promote experimentation with new (and renewed) rites of passage. State-level service years are just one piece of the broader puzzle — but, still, they’re an important piece.

A generation from now, it’s possible we’ll look back on this moment as an inflection point for reconstituting the adult transition to become the great connector, not the great sorter. If we do, it’s possible we’ll look at the expansion of state service years — first an experiment in a few states, then a policy wave in dozens more — as a key contributor to this transformation, helping hundreds of thousands of young people each year cultivate relationships with friends from wildly different backgrounds than their own.

Today, we have a window of opportunity to grow state service years to become a policy movement that helps reshape the adult transition. It’s time for states to seize the moment.

If you are a legislator, activist, expert, or journalist looking to help promote this policy in your state, check out (and share) the kit — and please get in touch!